Growing Up Xicana by the Sea

When I was a child, I had one wooden dresser drawer, a broken one, the last one on the very bottom, the one my mom assigned “just for your things” she had said. My family of four lived in a one-bedroom apartment, the kind where the bathroom lives inside the bedroom and the bedroom has a sliding door that latches to close, so having a drawer all to myself for “just my things” that didn’t include my clothes, felt like a real luxury. My drawer had nicely stacked folders of my Rocky and Bullwinkle coloring pages, cheap oil crayons that barely left behind any semblance of color, a purple “trapper keeper”, with Velcro edges, my mom had found at a yard sale, a plastic box of pencils, and notebooks full of just my handwritten name. Tannia Esparza. Tannia Esparza. Tannia Esparza. Page after page. Line after Line. Like I was trying not to forget myself. That's how it was for almost all of my childhood- words had found me and even if I didn’t say them out loud, they gathered into an arsenal of knots in the back of my throat, later to be dissolved by the courage it took to use them.

My primary caregiver was my mother, who came to the U.S when she was eleven years old. Like many migrant people, her focus as a parent, was to meet her children's basic needs. She had little time to spare for extras on many fronts. I went to elementary school in California, during the early 90’s, at a time when bilingual education was under attack, but still possible. I learned to eat, breathe and speak in Spanish first. So when it came time for school, I learned to read and write in Spanish first too. I loved all the workbooks, but my favorite one was the blue one, "El Sol y La Luna". I enjoyed tracing the big letters on their dotted lines- the b's and d's were my favorite because they had round bellies. I excelled so much that I was placed in a grade above, during language arts sessions, still completely in Spanish. I delighted in our class trips to the school library, where we walked sloppily in single file just so the librarian would read to us. I didn't always understand the words in English, but I loved the lull of the librarian's voice sounding out dialogue, changing her tone to emulate the characters in the picture books she’d read to us. I felt tender, like the journeyed in-between space your heart feels after waking from a nap.

One of the first books I owned was a gift from one of my father's Chilean soccer friends. I was about six years old. The fact that he was Chilean mattered because he was a different kind of immigrant than us. My dad's friend, had a fancy apartment and was fluent in English. I don't remember why this friend gave me a book, but I remember the cover was tan, with an image of a brown-haired boy and his grandfather wearing sweaters. I remember writing my name in my crooked handwriting on the inside cover. I was so proud. "Un Pasito y Otro Pasito”, by Tomie de Paola was the only book I owned for some time. It was the story of Ignacio, a boy who taught his grandfather, Nacho, how to walk again after he suffered a stroke, the same way Nacho taught his grandson to walk when Ignacio was a baby. I was drawn by the repetition of words in the book, by the way it began and ended in the same way, a cycle like a circle. The song I could feel in the book when I read it, so familiar, like the way my mother spoke to me in Spanish, the way we danced our cumbias at family parties or that recognizable feeling of longing for a way to fix things. At six years old, I had already suffered a great loss and I suppose I could feel that in the book too. I read and re-read the book over and over again, to myself and to my little sister, who learned to love it too. After a while the spine wore down, the pages wrinkled and my name faded from the inside cover. It was around this time, when I learned how to perform "quiet" well. Somewhere, in-between my mother's tears, her insomnia and my father's drunken shouting was a little Tannia, lying awake, taking it all in. Listening. Scanning for threats. Finding the nearest exit. Protecting. She dialed 911 only once and when they called back and dad answered, Tannia learned it wasn't always smart to say things out loud. So she kept quiet, taking mental and emotional notes, and having sooooo many feelings.

I started learning English and was placed in the "gifted program". I didn't know what college was at the time, but my mother would always say "You will go to college, so you won't have to clean people's houses like me." I remember strategizing to sound the words out in Spanish to spell them correctly in English. Words like "because" and "people" were hard to spell in English, but easy to remember in Spanish if I sounded them out like P-E-O-P-L-E and B-E-C-A-U-S-E. Every correctly spelled word, a carefully revised choice in a paragraph, and one step closer to college, whatever that was. I slowly left behind my strategies and I no longer needed them. English came as easily as Spanish had until they would trade places and I had to work harder to remember the meaning of things in Spanish. That's when the stakes grew higher and I took longer to finish my homework. I stopped enjoying the b's and the d's as much. I focused my attention to getting good grades and meeting standards, which later morphed into my own and no matter what I did, I could not meet them.

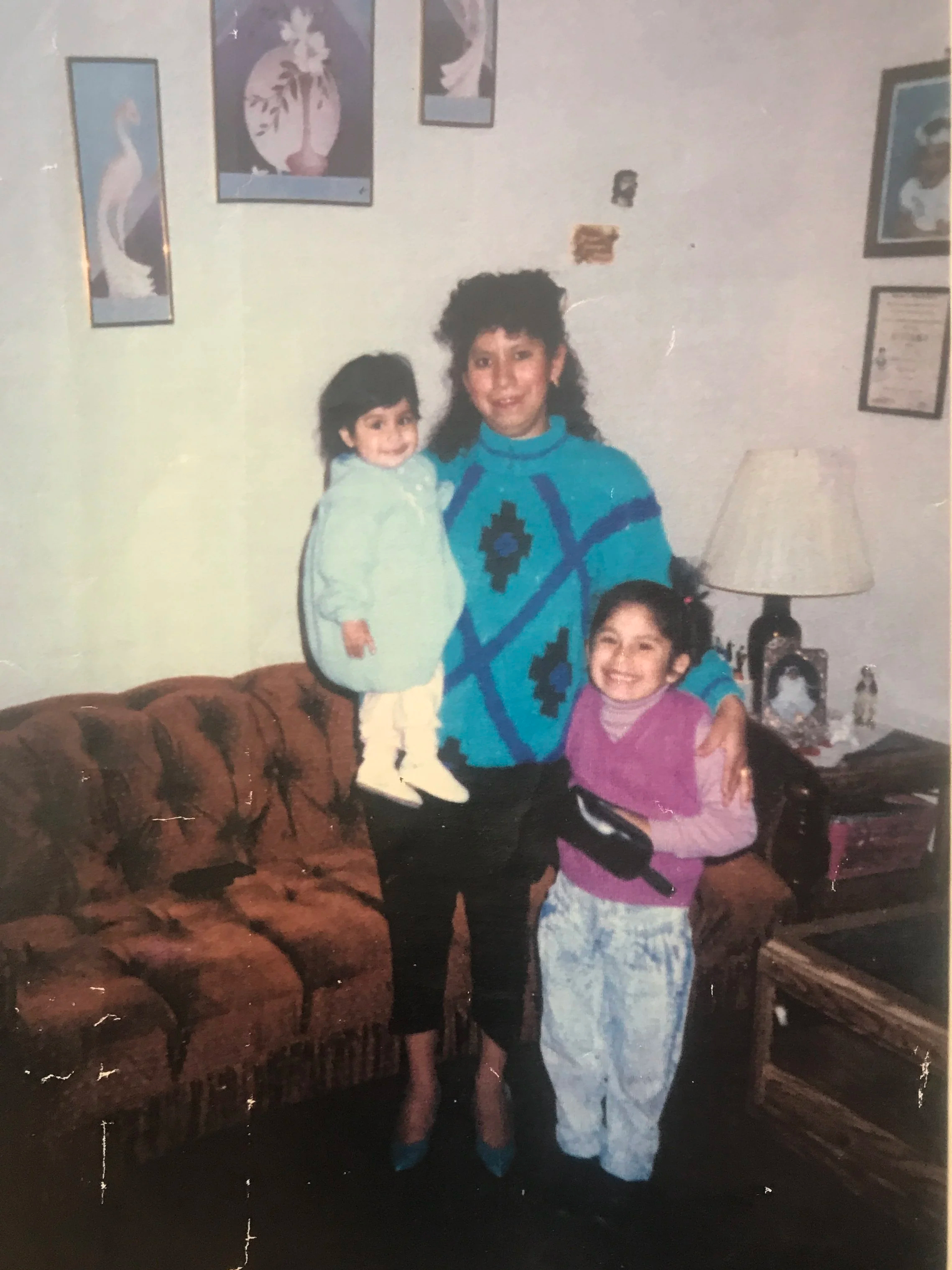

In second grade, my father finally left us. My mother worked too many jobs and began taking evening classes at our community college. Tia Norma, my mom’s youngest sister, who felt more like my older sister, moved in with us. Tia Norma had just graduated high school and attended community college with my mom. Her youthful spirit was palpable- she talked really fast, and moved in big dramatic gestures. Like my mother, Tia Norma was also a runner, but unlike my mother her English was really good. We lived in an all-girl house and it was so much fun. To make ends meet, my mom, Tia Norma, my sister and I would re-sell used items at the Swap Meet. On Saturdays we would wake up early and head to the yard sales in wealthy neighborhoods to buy goods that could be re-sellable. Things like used Nintendo’s, TV’s, and VCR’s were highly sought after and made enough money to meet our grocery quote for the week. On Sundays we would make the two-hour drive to the Nipomo Swap-Meet. During those long drives, my sister and I sat in the back while our mother drove our light blue, 1986 Chevy Nova, packed to the brim with all our goods, while my Tia Norma Dj’d from the passenger’s seat, blasting Pandora’s Juan Gabriel Medley.” At the top of our lungs we all sang:

“Si nosotros nos hubiéramos casado,

Hace tiempo como yo te lo propuse,

No estaríamos sufriendo ni llorando.

Porque el humilde amor que yo te tuve, caray cuando te tuve, caray cuando te tuve.

Ahora soy yo, quien vive feliz,

Formé un hogar cuando te perdí.

Después, después yo te olvide y te perdone.

Y no puedo hacer, ya nada por ti, ya nada por ti, ¡ya nada por tiiiiii!”

It was an understood knowing among all of us that we sang this song to my father, who couldn’t be helped anymore, and missed out on the joyful little family we were becoming. Every weekend was the same, we woke up early, we drove, we ate cinnamon rolls for breakfast and sang our feminist anthem. Surely, neither our car nor our house had ever laughed so much. A little over a decade later, I would become the lead singer of a queer Mariachi Band where I’d find out just how surprisingly strong a soft talking, singing voice could be.

So many of the adults in my life who were supposed to care for me and teach me, failed me, but I am possible because I was mothered by the hands of many matriarchs. Armida was one of them. My mother met Armida at "La Cocina de Tere" a small family-owned Mexican restaurant where she waited tables. The owners often allowed my mother to bring me to work when she couldn't find childcare. I'm told I had a booth and coloring books to keep me busy. No one ever described what the restaurant looked like, but I can imagine my mother, who was a long-distance runner back then, with her skinny legs and big brushed out curls walking around in black pants, white apron around her waist surrounded by a sea of red colored booths and chairs (don’t know why, but in my mind, the restaurant seats are red). Me, a 15-year-old going on 16, toddler stationed in a corner booth by a window taking in bright Santa Barbara sunlight, crayons all over the place and people checking in on me. That’s how I imagine this arrangement going when one day, Armida, one of my mother's regular customers, asked who I was. Armida quickly learns that my mother was mostly on her own and offered to care for me while my mother was at work. Armida was probably in her sixties and still so "cha cha". She wore a short-peppered bob haircut, copper brown lipstick, big dark sunglasses and navy-blue linen pants- a Xicana by the sea. She and her husband, Victor, lived on a boat at the Santa Barbara Harbor. Armida and I used to play all day by the beach, making sandcastles, dipping in the public pool next to the harbor, smelling like Avon sunscreen, and clam chowder. We would go on boat rides - my face full of long curly hair stuck to the edges of my poorly applied lipstick, blown by the wind on chapped happy cheeks.

An illustration of Armida and I (bottom left hand corner) from a story I narrated during an online gathering in 2020.

One day, my mother took me to a house full of green succulent plants, the kind that hang from tall ceilings and dangle. She said we were going to visit Armida. We were in the car for a long time. "How come we aren't going to the boat?" I asked. "Because Armida is somewhere else," my mother answered. When we got to the plant house I realized Armida was indeed somewhere else. Her green talking parrot was there on a perch by a window. But nothing else felt familiar, not even Armida. When I walked into her bedroom, Armida was lying on a small bed covered in white blankets and a winter hat around her head. She was thin and still smiling. No copper lipstick, no big sunglasses, no wind, no hair. She held my hand and asked me what I was doing in school ( I had just started pre-school). I told her I learned the ABC's. My mother told me to sing the ABC song to Armida, but I couldn't. I couldn't sing. I couldn't say. No one told me it would be the last time I'd ever see Armida again, but I knew. I knew and I couldn't sing to her. Sometime later I thought, I knew and I wouldn't sing to her. The difference between couldn't and wouldn't is the choice. Even then, I chose. I chose to keep the knot in my throat to myself. I chose not to say goodbye. I chose to keep us both on her boat, surrounded by salty wind in our face- Xicanas by the Sea.

Santa Barbara Harbor at Sunset

Armida didn't give me books. She didn't read to me. We never wrote together. She gave me sand in my toes, places to go, seafood to crave, sunsets to remember, space to let the light in and notice, life to live. Thanks to her, I never stopped noticing. Even when I kept what I noticed to myself, in the quiet corners of my broken wooden drawer, etched in the crooked letters of my name in those lonely notebooks, I grew the skills of loving the world fiercely, which translated into learning her contours, bracing for the noise, finding home among the underdogs, and the ones who ask questions because I had someone who taught me how to swim in the watery art of being alive.

My childhood had very little sparkle, but the women who raised me, like my Mother and Tia Norma, and Armida, taught me to feel and to notice the great big world around me. In those hard and crucial early years, their love was creative practice. They prepared me for learning, for finding life in the dark days that would still come, and to relish the imprint left behind by the tiny miracles of everyday possibility.

REFLECTION:

The kind of communicator/writer/reader I’ve become is someone who, beyond anything else, practices presence enough to notice. I’m observant, empathetic, and deep feeling. I knew I wanted to tell the story of Armida, the central role of being raised by matriarchs and the role of living through trauma. The brainstorming exercise was really helpful in helping me recall various moments in my childhood that gradually built me into being a more and more quiet child, all the while becoming more and more feeling, more and more observant, and louder and louder with my feelings, which is perhaps the greatest insight I’ve had through the course of this project. I thought about starting the narrative with the first part of Armida’s story, but I didn’t feel like I could do us justice by breaking it up. Instead, I decided to dig deeper for an opening that would help draw out an image from my childhood that carried enough meaning to keep unraveling the thread.

It was challenging to take things out or not include other parts of my literacy journey like my love for Latin American poetry or the joy I experience when reading literature in Spanish. It was also challenging to figure out the sequence of how I wanted to tell the story. My memory of childhood gets jumbled in some places. It was difficult to decide if/when I wanted to be chronological (which feels boring to me), and when the timeline didn’t matter as much as the message and intention behind it. I opted for a mix of both. One could argue that anytime we remember the past or imagine the future we are treading the waters of time travel and if we can do that, then time has no bounds. This knowing, gave me permission to allow my memories to flow as they came. The timeline didn’t need much editing after I allowed myself to do that. Because I understand that my audience may not catch the very specific cultural and contextual references in my narrative, I opted for a blog style page that could easily include referential multimodal elements to either support understanding or pique someone’s potential curiosity. I choose to add an audio element to this because I feel like this narrative is better understood while read out loud. I also think it drives the point home that this noticer learned to use her voice, eventually.